I went to New Haven, Connecticut, the home of Yale University, to see the Portrait of John Wilmot and hear a lunchtime public talk by a student gallery guide, Adam Chen. He described the representation of Wilmot as Commissioner for compensation for British losses in the American War of independence up to 1783. The portrait is hung in the Long Gallery at the Yale Center for British Art. Opposite, looking across at it, is a full-length portrait of its painter, Benjamin West, President of the Royal Academy of Arts.

I was able to read correspondence between the painter, West, and the sitter, Wilmot, that are held at Yale Library. Wilmot didn’t want just a portrait for his family, but rather a celebration of the loyalty of those British subjects who remained loyal to the Crown rather than join the American revolution. West, originally from Philadelphia, who had become the Royal History Painter, responded with the portrait and allegory in one painting (January’s blog).

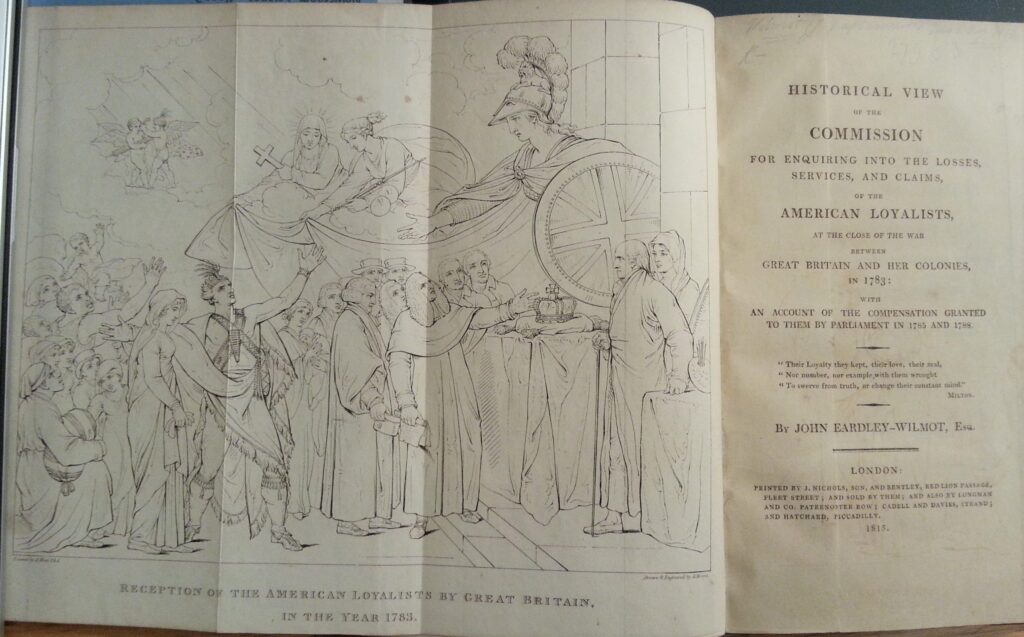

The engraved Allegory (above) became the frontispiece to Wilmot’s book about the Commission . It was called ‘an outrageously self-serving fiction’ by Simon Sharma, in his book Rough Crossings about the experience of British blacks after Independence, because Britain did not give financial compensation equally to the different groups represented in the picture. Yet from the West/Wilmot letters, the picture’s purpose was to show loyalty rather than compensation: West brought women and children, commoners, blacks and a Native American all into the picture.

Wilmot’s portrait has a parallel with contemporary history. In 2019, Britain had a (non-military) rebellion against the European Union, the vote for Brexit. The ‘Remainers’ in Britain, and also those living in other European countries, feel let down by politics in the same way as the loyalists were. This time, there’s no financial compensation being voted by Parliament. Yet it’s unlikely that the President of the Royal Academy will make a portrait of Sir Kier Starmer, who led the Labour party opposition within Parliament; it is more likely that the losers will be forgotten.

West’s portrait of Wilmot has much British political history in it. It is sad that it was sold to Paul Mellon in 1970 and moved to America, rather than being in the London National Portrait Gallery. But there’s a small story to give a smile. The American State Department asked Mellon if it could be loaned the picture for its Diplomatic Reception Rooms.1 They believed – because of misattribution in the Auction catalogue – that the picture was ‘another version’ of Signing of the Peace between Britain and the United States that West had painted in 1783. But the Portrait of John Wilmot is a strong statement of loyalty to King George III – hardly the symbolism for the US Diplomatic Reception Rooms.

1 Correspondence held at the Yale Center for British Art