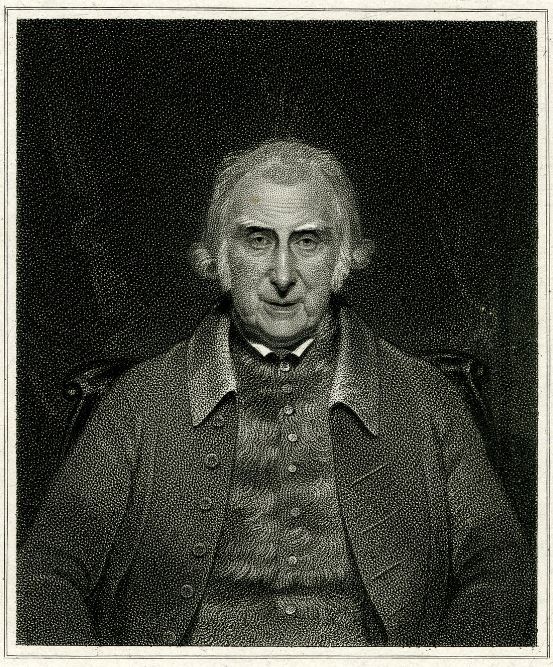

The General Register Office doesn’t usually provide humour, but the 1861 census shows a recorder finding the bare-knuckle prize-fighter Tom Sayers at 10 Belle Vue Cottages (later renumbered 51 Camden Street). He wrote, with nationalist delight, Sayers’ occupation as ‘Pugilist – Champion of England’.

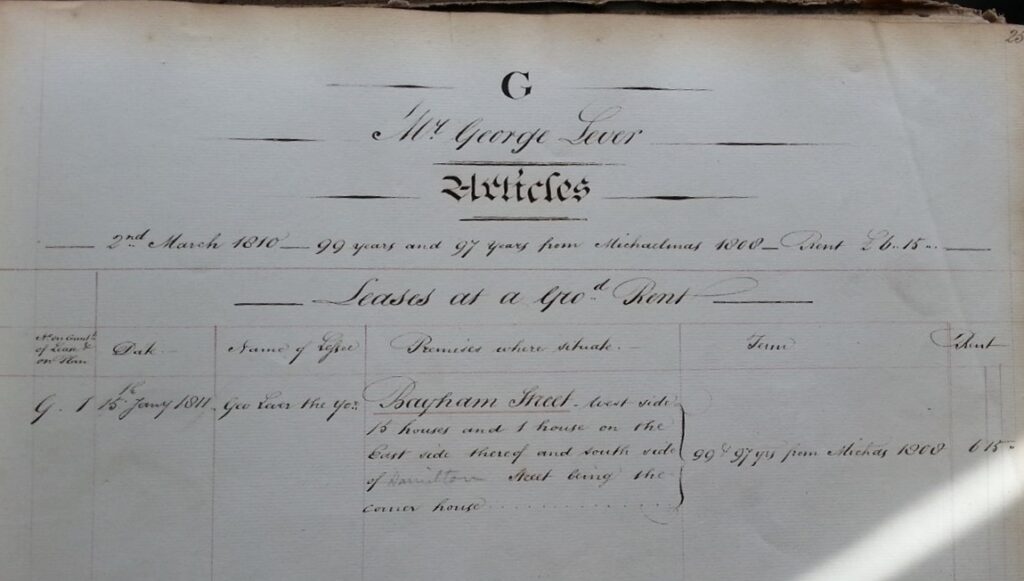

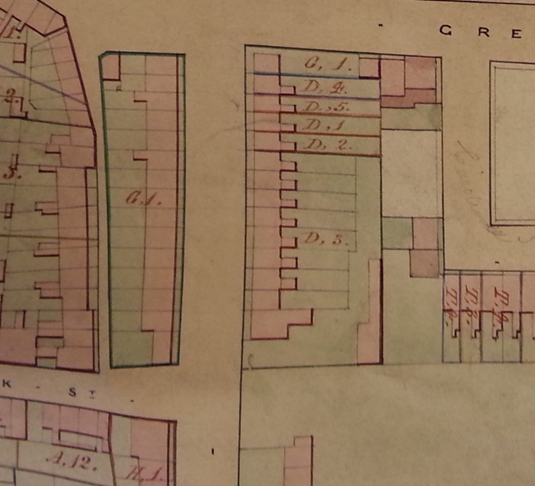

Sayers had come in the 1840s to Camden Town to learn and practise the trade of bricklayer with his brother-in-law, but quickly took up fighting for money. The 1851 census gives his address, with his then common-law wife Sarah and baby Sarah, nearby at 45 Bayham Street. In the spring of 1860, Sayers became a national celebrity when he held the American champion John C Heenan – who was taller, heavier and younger than Sayer – to a draw in their 42nd round. Sayers’ Wikipedia page has a delightful, if dubious, scrawled ‘Chalang’:

Camden Town was not the place for professional fights, which were usually held out-of-town to escape police attention. In Pierce Egan’s early history Boxiana or Sketches of Modern Pugilism (1829), only Tom Shelton is recorded fighting in Camden Town itself, and then just a couple of early scraps – ‘although inebriated, he backed himself for five shillings and a gallon of beer’ when he defeated Jem Carter in twenty minutes ‘in the road, near the sign of Mother Red Cap’. His second win was against ‘a big navigator, of the name of Brown, in Camden Town brick fields, having refused to pay a gallon of beer to his companions’. A Thomas Shelton was baptised in January 1800 at St Pancras Old Church, but there is no trace of his death locally.

Oddly, in 2002, English Heritage did not put its blue plaque on either of the addresses where Tom Sayers had lived, even though his will identifies his home as Bell Vue Cottages. Instead, it is on the house of a friend where Sayers was cared-for in the few days before his death, on the west side of the High Street near Kentish Town Lock. From there, a large cortege carried him away up to Highgate cemetery, as the nearby St Pancras burial ground at the Old Church was by then closed.